Around two years ago, I was still in graduate school, still in semi-early recovery (again), and still trying to navigate support groups and fat acceptance all at once.

As a recovery practice, I began getting comfortable with using the word ‘fat’ as a self-descriptor around in my shares at group and in conversations–until I was called out and told not to come back until I could figure out my language and how to stop saying ‘fat’ because it was triggering to others.

I understood that. I understand that for so many people, fatness is a fear, and that fear can coexist with a mental illness (like anorexia, bulimia, or body dysmorphic disorder).

But I was also grappling with the fact that societally, fat is set up to be an insult, and I was tired of that dynamic, especially in ‘recovery’ spaces. I wanted to reclaim the word and remove its pejorative use from my consciousness. So I did, in my speech, shares, and writing.

Fatphobia is insidious in virtually every corner of our culture, because it prioritizes the politics of desirability over health. This happens even in spaces that are meant for people in recovery.

Fear of fat or becoming fat is not a diagnostically supported symptom of body dysmorphia; it is a socially constructed symptom of diet culture that has trained people to value aesthetic desirability over health. Fatphobia still comes in so many forms, even in spaces that claim recovery. It sends the message that recovery from an eating disorder is possible, but only if it’s done while in a specific body.

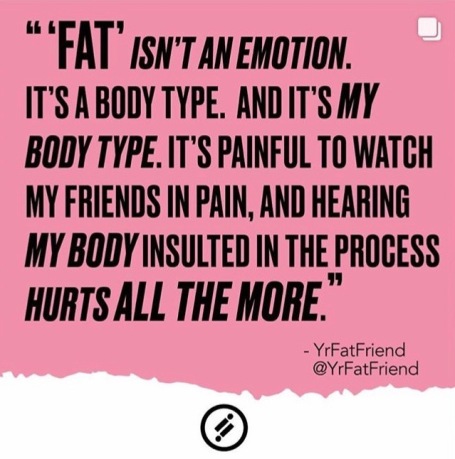

There are still so many recovery spaces that support the sentiment that it is okay and valid to not want to look like me. These same spaces are the kinds that have historically validated the notion that “fat” is an emotion, as if it can be removed from one’s consciousness embodiment the same way that sadness or contentment pass. My body type isn’t an emotion, and I can’t just get rid of it; in fact, I spent over half my life trying to do just that…and it was called an eating disorder.

Nobody wanted to call it that, though, because for most of my active illness I was in a body deemed aesthetically acceptable. How I got that desirable body wasn’t investigated, it was just assumed that I must be doing something right because my body was “right.”

The endless calorie deficit spreadsheets and the six to ten times a day I would weigh myself suggest otherwise.

I have learned and come to the conclusion that I am under no obligation to assuage thin peoples’ insecurity about the possibility of looking like me. I certainly have compassion for where they are and the ways that diet culture has manipulated them, but at the end of the day, my fat body will not be used as an example, will not shrink itself to make space for bias, and I do not and will not ever be responsible for the ways that someone’s triggers are justified at my expense.

It’s not anyone’s fault that they learned that fatness was evil, bad, immoral, lazy, or undesirable. At the exact same time, it’s not my job to soothe the deep-seated hate for my body and others like it. It’s that person’s job to unlearn, question, shift and not project what they were told about fat bodies, and theirs alone.

Fatphobia comes in the form of silencing, health concern trolling, food policing, making spaces inaccessible (and much much more), and ignoring that Health at Every Size is more than a movement; it is and has always been a well-documented and valuable scientific approach. Do not mistake Health at Every Size for HealTHY at Every Size (Thanks M for that one), because not every single body is healthy.

Thin bodies can be diabetic, have heart problems, or high blood pressure. Fat bodies can be anorexic, have osteoporosis, or be poorly nourished. No disease is exclusive to a body type. My weight alone does not guarantee that I will get sick, just like thinness alone does not guarantee health. My body has a GI disorder that is entirely genetic, and correlated to my mental illness (anxiety), also genetic.

What’s more, I don’t owe anyone in the world receipts for my health in order to claim recovery. I had to unlearn fatphobia completely on my own, just like I learned it from the beginning both blatantly and subliminally. The ways that it is STILL pushed upon me are an unnecessary burden, and inevitably do harm, but it is solely my responsibility to make sure that I don’t project that harm or that burden onto other bodies.

Same goes for fatphobic conditioning, comments and advice you may think is rooted in health. Unless that person is paying you for advice, save it. And even then (because some doctors literally get paid to fat shame people)–THINK–is this thoughtful? Helpful? Important? Necessary? Kind? The ways that fatphobia is expressed onto bodies, often (almost always) without their consent. What people fail to understand is that fatphobia and weight stigma itself is health-compromising, “good intentions” be damned.

If my body or the words I use to describe it are triggering to you, that has little to do with me or with disordered eating, and a whole lot to do with the potential work needed to dismantle anti-fat bias. Look within and examine unconscious stigma. What’s so terrible, scary and disgusting about being in my body? All I see when I watch this play out among fatphobic people, unconsciously or not, is that what they’re truly afraid of is losing is 1) their perception of thin as superior, 2) the indignant self-righteousness of “health and wellness”, and 3) their ability to feel power when they make anyone over a size 16 feel shame.

It can be really hard and terrifying for someone to come along and burst what’s familiar to you, but get used to it. It’s not my body or the fact that I say FAT that makes them uncomfortable, it’s the fact that the same science that privileged thin existence for all of the 20th century is just now concluding that I am capable of health and deserving of recovery.

Regardless of your fear, my body is still here and I still love it for what it is; in fact, I have done more health-promoting behavior holistically (mental, spiritual, physical, etc.) in this body than I have in my entire life. If that’s a threat to your joy or your pursuit of desirability; that baggage ain’t mine. Stay mad.

xoxo